Montford Thomas Johnson [1] (Nov. 1843 - Feb. 17, 1896) was Chickasaw and a cattleman who lived in Indian Territory, what is now the present-day state of Oklahoma. Montford Johnson was a well-known and respected entrepreneur, noted for his successful ranching operation that spanned a large area of central Oklahoma, including parts of what would eventually become Oklahoma City.

Family Background

Montford Johnson's father, Charles "Boggy" Johnson, was an English Shakespearean actor. Boggy Johnson came to the United States when he was 19 years old and traveled in the South with a theater production.

Boggy Johnson married Chickasaw citizen Rebekah Courtney Johnson, Montford Johnson's mother. She was half Chickasaw and half Scottish. After marrying, Rebekah and Charles Johnson migrated with the Chickasaws to Indian Territory during the Chickasaw Removal [2, p. 9]. Once in Indian Territory, they built their home north of Tishomingo, near present-day Connerville, Oklahoma.

Early Life

Montford Johnson was born in November 1843, about two years after his older sister, Adelaide Johnson. A few months after he was born, his mother became ill with pneumonia and died. Boggy Johnson, distraught by his wife's passing, decided to take the children and return back east [2, p. 15]. As it was customary for Chickasaw families to take in motherless children and raise them as their own, Boggy Johnson's Chickasaw in-laws insisted on raising the children. He left without siblings Adelaide and Montford Johnson, leaving them in the care of their grandmother, Sallie Tarntubby. Montford Johnson grew up with his grandmother's family, learning Chickasaw traditions and how to take care of livestock. He attended school at the Chickasaw Manual Labor Academy [2, p. 18]. There, he learned farming techniques necessary to produce successful crop yields. Montford Johnson lived under the care of his grandmother Tarntubby until her death in 1858. At the end of that school year, he moved to the home of their next nearest relative, Sallie's half-brother, U.S. Army Capt. Townsend Hothliche [2, p. 19]. He was stationed at Fort Arbuckle, and had a house nearby on the south bank of the Washita River. On a trip to Fort Arbuckle, Adelaide Johnson befriended the Campbell family, who was living at the fort. The Campbell’s moved to Indian Territory when the father, a U.S. Army sergeant, was transferred to Fort Arbuckle, near present-day Davis, Oklahoma. Adelaide Johnson fell in love with and married Michael Campbell, one of Sgt. Campbell's sons [3, pp. 1491-1492].

Civil War Years

The outbreak of the Civil War forced major changes in Indian Territory and affected Montford Johnson and his family. The Union Army evacuated Indian Territory moving into Kansas, allowing Confederate troops from Texas to occupy many of the territory’s forts. The Chickasaws sided with the Confederates and also supplied troops to maintain order and defense. Michael Campbell joined the Chickasaw battalion as a major and spent much of the war away from home or stationed at Fort Arbuckle. Montford Johnson oversaw the duties of the homestead and worked as a partner with Michael Campbell. It was during this time that Montford Johnson met and fell in love with Adelaide's sister-in-law, Mary Campbell. In fall 1862, they were married. A year later, Edward Bryant (E.B.) Johnson, Montford Johnson’s first child, was born [3, p. 1490].

After the drowning of Michael Campbell, Montford Johnson became the head of the homestead, which included his sister's young family.

In July 1865, the Chickasaws were officially the last Confederate tribe to surrender, marking the end of the United States' greatest tragedy [4].

The Chickasaw Nation was devastated. Chickasaw seminaries and academies converted to barracks or hospitals and would not be returned to teaching until the 1870s. Confederate debts incurred during the war were worthless, leaving the Chickasaws largely impoverished [5].

Montford Johnson Starts Ranching

With Montford in charge of the homestead, he set to work getting the ranch business in order. First, he purchased branding rights from his relatives. Second, he made an agreement with the men of the neighboring farms to round up cattle that had been set loose in the mountains during the war so they would not be taken by warring armies. Montford Johnson offered to pay for each of the cattle he found in the mountains, and any unbranded cattle would be his outright [2, p. 33]. While rounding up cattle, he noticed the wild cattle desired salt. Using salt licks, he devised pen-traps that allowed cattle to enter but did not allow them to escape. This greatly increased the number of cattle he was able to corral with relatively little effort. Around this time, Montford Johnson hosted his friend Jesse Chisholm on a buffalo hunt on the western range of Chickasaw territory, south of present-day Norman, Oklahoma. At that time, the area was largely undeveloped, and Montford Johnson thought it would be perfect to range cattle there [6].

Chisholm suggested Montford Johnson negotiate agreements with the local tribes Johnson was able to make a deal with the tribes that allowed him to use the land as long as he did not hire white men as ranch hands. Montford Johnson began his first ranch in the spring of 1868, taking a team of men to [Walnut Creek], the same location of the buffalo hunt. He placed ranch hand Jack Brown in charge of the Walnut Creek Ranch [7].

Montford Johnson Establishes Additional Ranches

Around 1870, cattlemen from [Texas] stopped using the Shawnee Trail and began driving their herds to Kansas on the Western Shawnee Trail, what would become the Chisholm Trail [8]. In 1871, Montford Johnson's sister, Adelaide Johnson, married her second husband, Jim Bond, a trader and stockman. Montford Johnson settled his business with her (which was started while he oversaw her homestead during the war), giving her 15 cows and calves and several steers, worth approximately $1,100 at that time. Montford Johnson was pressed by distant relative Chub Moore to take in several orphans. He agreed, taking in seven children, two of whom were almost adults [2, p. 80]. To lessen the burden of adopting so many children, Adelaide Johnson agreed to take two of them, and “Granny” Vicey Harmon (a family friend and Chickasaw) agreed to take three of the children. Montford Johnson and Mary Johnson took in the last two. Vicey Harmon had lived with her Cherokee husband, Sampson Harmon, about 10 miles west of the Camp Arbuckle Ranch until his death. Montford Johnson declined to help her with the trading post, but eventually convinced her to take charge of a new ranch at Council Grove, making her the first permanent resident of the Oklahoma City metro area [2, p. 83]. In the spring of 1874, Charley Campbell, a brother of Adelaide Johnson's late husband, became a partner of Montford Johnson's and took over the Walnut Creek Ranch.

.jpg.aspx?lang=en-US&width=400&height=579)

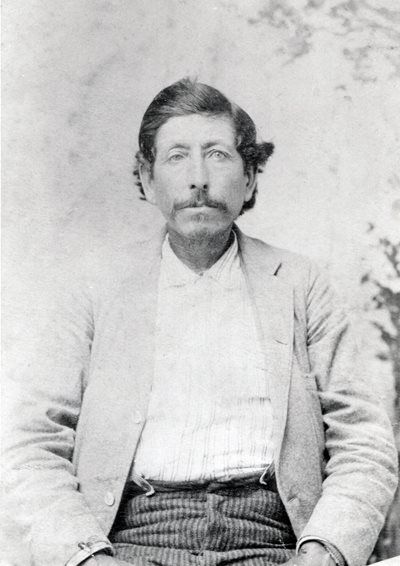

Photo courtesy of the family of Montford Johnson

Boggy Johnson Returns

In the summer of 1877, Montford Johnson received a letter from his estranged father. They arranged to meet at a hotel in Denison, Texas. The men spent two days catching up and telling their respective stories, though Montford Johnson found it odd that his father had not been able to contact them up to that point. The visit did offer an important opportunity for Montford Johnson. There were a number of First Americans, from the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Arapaho, Comanche and Caddo tribes captured in the Red River War who had been taken from Fort Sill to Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida [9]. The conditions of the 300-year-old fort were poor. Boggy Johnson claimed to have many friends in Washington D.C., and Montford Johnson thought a trip to St. Augustine might prompt Boggy Johnson to ask those friends to help improve conditions for the prisoners [2, pp. 116-120].

Boggy Johnson contacted Montford Johnson the following summer, and they planned to meet in Jacksonville, Florida. Montford Johnson was accompanied by Charley Campbell and Montford Johnson’s son, E.B Johnson. They rode to Atoka, Oklahoma, and boarded the train. For E.B. Johnson, it was his first train ride, and he was anxious on the first leg of the journey, convinced that they would crash. When they arrived in Jacksonville, E.B. Johnson met his grandfather Boggy Johnson for the first time. The following morning, they went by boat to St. Augustine and to the fort. There, they found the condition of the First Americans to be inadequate. Montford Johnson received permission from Capt. Pratt – a Civil War veteran who went on to found the Carlisle Indian School – to host a barbecue for the prisoners. Montford Johnson sent his son E.B. Johnson to find a cow for the feast. After finding a cow, E.B. Johnson had a butcher prepare and bring the beef to the fort. The prisoners were especially grateful to E.B. Johnson for bringing the beef. There was nothing more Montford Johnson could do in Florida, but after the trip, Boggy Johnson went back to Washington D.C. to work with his contacts [2, p. 120].

Montford Johnson's Ranching Continues

Montford Johnson returned to his ranches and his son, E.B. Johnson, returned to school in Tishomingo, Oklahoma. Montford Johnson's Camp Arbuckle homestead was in the vicinity of the growing town of Johnsonville. The rancher became uncomfortable with the more crowded conditions of the area. All lands in Chickasaw territory were held in common, so there were no defined properties. The growing town brought in more and more settlers. In 1878, desiring a wider open locale, Montford Johnson worked out a trade with his friend, Caddo Bill Williams, exchanging eight geldings and an old stallion for Williams' ranch east of Snake Creek, near Old Silver City (just north of present-day Tuttle, Oklahoma [3, p. 1491].

After Montford Johnson moved his family to Silver City in the fall of 1878, Adelaide Johnson and her husband, Jim Bond, moved nearby. They built their own home a couple miles west of the Chisholm Trail on the southern bank of the South Canadian River. Their homestead location was a suitable place for crossing the river, and cattle drivers often stopped at their home for the night. A major problem for Montford Johnson during the 1870s and 1880s was the threat posed by Texas cattle being driven north to the Kansas railroads. The Texas longhorns brought ticks that carried bovine babesiosis [Texas cattle fever] to Montford Johnson's herds. While the longhorns were immune, Montford's cattle were not, and he had difficulty keeping his herds separated from the Texas herds. This was a problem because cattle fever was known to wipe out entire herds. In August, 1880, Montford Johnson’s wife, Mary Johnson, became ill with a fever. The doctor at Ft. Reno, 25 miles away, was summoned. He reported that she was suffering from [ergotism]. Mary Johnson died on Aug. 27, and was buried in the family burial grounds at Silver City [10]. Upon hearing of her death, Boggy Johnson asked to have his grandson E.B. Johnson join him in [New York City] to go to school. Montford Johnson agreed, and his son E.B. Johnson soon left to join his grandfather. Montford Johnson visited his son several times in New York City, and on a visit in late 1882, informed his son of his intent to marry his cousin-in-law, [Addie Campbell]. Addie Campbell was much younger than Montford Johnson, and E.B. Johnson objected to the marriage. Montford Johnson was unmoved, and his son eventually relented. By the 1880s, Montford Johnson was grazing his cattle on land between [Pottawatomie] country to the east, the [North Canadian River] to the north, the [Wichita Reservation] to the west and the Washita River to the south. Conflict quickly arose when settlers known as “[Boomers]” made attempts to enter the [Unassigned Lands] prior to the [Indian Appropriations Act of 1889].

Edward Bryant (E.B.) Johnson Takes Over Montford's Business Affairs

E.B. Johnson returned from New York in February 1885 and immediately set to work getting his father Montford Johnson’s businesses in order. Montford Johnson was a generous man, having allowed numerous lines of credit through his store in Silver City. He offered his son a 50% share of the Silver City store, and he set out to collect some of the overdue bills, which amounted to approximately $15,000. E.B. Johnson collected cash and livestock as payments for the various debts owed to the Silver City store [2, pp. 180-182]. His actions made Montford Johnson’s business partners uneasy, and they decided to end their partnerships. E.B. Johnson assisted closing out business with their partners, which included Jim Bond, Montford Johnson‘s brother-in-law. Montford Johnson and E.B. Johnson continued ranching despite continued encroachment by Boomers. New ranches were being established along their periphery, creating sometimes dangerous situations. Occasionally, they would find cattle that had their brand covered up by a new brand, an obvious sign that cattle had been stolen [2, pp. 190-191]. On one occasion, Montford Johnson and E.B. Johnson were fired upon after one of their men, [Adam Ward], was shot in a dispute over a steer. There were numerous similar incidents in which ranchers were killed in arguments over cattle ownership.

Land Rush of 1889

The Indian Appropriations Act of 1889 stated that 1.8 million acres of the Unassigned Lands were to be opened up to settlement for claimants, in what became known as the Land Rush of 1889 [11]. Some of Montford Johnson's holdings were in this region, but this occasion had been foreseen. In preparation for the land rush, the Army ordered all cattlemen to remove their livestock from Oklahoma Territory. E.B. Johnson gathered some men and began herding his cattle back into the Chickasaw Nation. During this cattle drive, the herd and several of E.B. Johnson's men were captured by a group of soldiers and were to be taken to Fort Reno. E.B. Johnson caught up to the herd and forced the soldiers to retreat. After a while, a large group of cavalry placed the entire group under arrest. E.B. Johnson and his men were taken to the fort, where he discussed the issue with fort authorities. They decided the soldiers had acted on contradictory orders. E.B. Johnson was able to gather the herd and they departed, making it to Chickasaw Nation lands the morning of April 22, just hours before the Rush was to begin [2, pp. 212-215].

Photo courtesy of the family of Montford Johnson

Late Life

With the land run, as well as the new barbed wire fencing-in of the prairie, Montford Johnson and the family had defined areas of land they controlled [12]. Despite these major changes, they continued the business as usual. The dramatic increase in population also meant towns were growing. Montford Johnson, along with friends and family, soon became founders of several banks in Chickasha and Minco, Oklahoma. Montford Johnson remained primarily interested in ranching and continued to seek new lands to graze his livestock. He established a lease agreement with the Kiowa, Comanche and Wichita tribes. The lease proved to be a difficult agreement. Inconsistent positions of the federal government concerning leasing of First American lands as well as cattle rustling made the lease a failed venture. After two years of trying to succeed on the lands amid legal battles and significant livestock losses, Montford Johnson consolidated his herd back to his ranches that were clearly inside the Chickasaw Nation. He attempted to recover his losses from the federal government, but never received compensation [2, pp. 250-253].The Dawes Commission was formally established March 3, 1893, with the intent of allotting the Chickasaw Nation lands into holdings owned by individual Chickasaws. Montford Johnson considered the commission to be a treachery, especially after their apparent stonewalling over his losses in the leased district. Most distressing was the fact the commission's proposals forbade Chickasaws from purchasing more land than was allotted, though white settlers were not restricted from purchasing as much land as they pleased. Despite much protest from the Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations, the Commission persisted [2, pp. 237-237,249-252].

Death

Montford Johnson suffered from poor health for many years, including malaria. He made several trips to Eureka Springs, Arkansas, and took various medicines to try to alleviate some of his ailments. In winter 1895-1896, Montford Johnson suffered from numerous ailments at once, and after being bedridden for several months, died Monday, Feb. 17, 1896. The following day, every business in Minco closed to show their respects, and the headline of the Feb. 21 issue of the Minco newspaper read "A Good Citizen Gone." He was 52 years old. Montford Johnson was buried in the Silver City cemetery with his first wife, Mary Johnson. His son E.B. Johnson took over his father's affairs and looked after his numerous younger siblings, most of whom were still children. Addie Johnson, Montford's widow, died in 1905, and E.B. Johnson arranged for her to be buried next to Montford Johnson [2, p. 267].

[1] C. N. M. Relations, "The Chickasaw Rancher," Chickasaw Nation Montford, The Rancher, [Online]. Available: http://www.chickasawrancher.com/Cast/Martin-Sensmeier.aspx. [Accessed 25 10 2021].

[2] N. R. Johnson, The Chickasaw Rancher, Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2001.

[3] J. Thoburn, "A Standard History of Oklahoma," 1916. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books?id=q4E_AAAAYAAJ&q=montford+t.+johnson&pg=PA1491#v=snippet&q=montford%20t.%20johnson&f=false . [Accessed 20 8 2021].

[4] C. TV, "Civil War and more Broken Promises," [Online]. Available: https://www.chickasaw.tv/events/civil-war-and-more-broken-promises . [Accessed 20 8 2021].

[5] T. Leahy, "Ranching, American Indian," Oklahoma Historical Society, [Online]. Available: https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entryname=RANCHING%E2%80%93AMERICAN%20INDIAN . [Accessed 20 8 2021].

[6] N. Kingsley, "The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture," Oklahoma Historical Society, [Online]. Available: https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=JO012. [Accessed 20 8 2021].

[7] N. Kingsley, "JOHNSON, MONTFORD T. (1843–1896).," Oklahoma Historical Society, [Online]. Available: https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=JO012 . [Accessed 20 8 2021].

[8] S. Dortch, "Chisholm Trail," Oklahoma Historical Society, [Online]. Available: https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=CH045 . [Accessed 20 8 2021].

[9] C. d. S. Marcos., "Plains Indians," National Park Service, [Online]. Available: https://www.nps.gov/casa/learn/historyculture/plains-indians.htm . [Accessed 20 8 2021].

[10] E. Sutter, "Vanished Silver City Burial site of Montford Johnson," 31 10 2001. [Online]. Available: https://www.oklahoman.com/article/2760683/vanished-silver-city-burial-site-of-montford-johnson . [Accessed 20 8 2021].

[11] B. Blackburn, "Unassigned Lands," Oklahoma Historical Society, [Online]. Available: https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=un001 . [Accessed 20 8 2021]. [12] D. Everett, "Barbed Wire," Oklahoma Historical Society. , [Online]. Available: https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entryname=BARBED%20WIRE . [Accessed 20 8 2021].